Why Effective Head Protection Should Also Protect Against Rotational Energy

Helmets generally provide too little protection against offset blows. The Mips safety system was developed to deflect the dangerous rotational forces that occur with an offset impact. The Mips technology has already proven itself over many years in various activities such as cycling, skiing and motor sport.

When something hits your head, it rarely hits exactly in the middle. The impact is far more often off center or at an angle. A protective helmet does protect against linear forces, but a glancing blow can also cause tangential forces between the helmet and the skull that turn the head. The rotation can cause significant damage because the brain is very sensitive to rotation. The Mips safety system for industrial safety helmets can provide additional protection against this. Max Strandwitz, CEO of Mips, told GIT SECURITY what the effects of rotational energy can be on the human brain, and how the Mips safety system protects and deflects this from the head.

GIT SECURITY: Mr. Strandwitz, Mips is a name that has been known and established in riding, cycling and motorsport for a long time. Mips recently started a cooperation with Uvex to provide protective helmets for the German market fitted with the Mips safety system. But why is the system also ideal for industrial protection?

Max Strandwitz: The helmet technology company Mips is known for its products for sport and motorcycle helmets and is also very popular with skiers and cyclists. We have now joined the leading manufacturers of personal protective equipment (PPE) to integrate the Mips safety system into protective helmets. Our aim is to better protect the head by deflecting damaging rotation that is caused by an offset impact, for example, when a worker falls or is hit by a falling object. This will reduce the risk of brain injury.

Those who spend a lot of time on building sites know that head injuries can be part of the job. They are mostly light impacts, but can sometimes be harder blows. The most frequent accidents are impacts from the side, falling objects, slipping, tripping or falling. Head impacts do not only happen in a straight line; more often, they have an offset impact angle that can cause the head to rotate. In spite of the widespread and mostly obligatory use of safety helmets, building and industrial workers are always at risk of head injuries, including various axonal injuries and concussion.

That is why it is important to understand head injuries. The term ‘head injury’ covers a multiplicity of injuries that can occur to the scalp, the skull, the brain as well as the tissue below and the veins and arteries in the head. Injuries to the brain that are caused by accidents or physical force are known as traumatic brain injury (TBI). A TBI can be caused by an impact, or a vibration of the head, or a direct blow to the head that moves the head and the brain rapidly to and fro.

Traumatic brain injuries occur in many forms. The most common are light skull-brain traumas or concussion. If you bang your head on the cabinet door, fall over, or injure yourself playing sport, this can lead to a slight trauma, the most common of which is concussion that covers up to 75 % of all traumatic brain injuries. These injuries are much more common than you would think; 50 % of all serious injuries are not diagnosed or remain undiscovered, and 90 % of the diagnosed serious injuries are not accompanied by unconsciousness.

Rotational energy is generated by a side impact on a safety helmet, as you just explained. How is this transmitted and what significant effects does it have on the human brain?

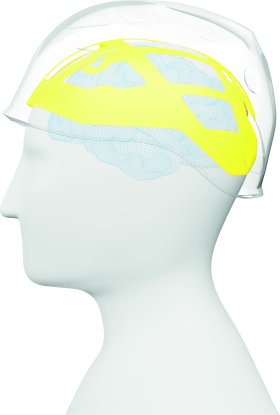

Max Strandwitz: The human brain is a fascinating construction – but sensitive, and in particular to rotation. Almost all head impacts create a turning movement that stresses the brain matter and can lead to light or serious brain injuries. The brain and the cerebrospinal fluid fill most of the skull. Both the brain matter and the fluid are almost impossible to compress, so the brain does not move much when there is a straight impact. A turning movement of the head though can cause the rotation of the brain within the skull. This can lead to a relative movement between the skull and the brain because the shear stiffness of the brain and brain fluid is low, which can in turn lead to damage to the brain matter or a rupture in a blood vessel, which can cause a traumatic brain injury.

There have been standards that a safety helmet should comply with in various situations for a long time. Among them are EN 397 for industrial head protection, EN 12492 for climbing helmets and EN 14052 for high-performance industrial protective helmets. Are these standards too low in your opinion and, if so, why?

Max Strandwitz: Traditional protective helmets were developed and tested for straight-on impacts and protect against injuries like broken skulls. They are however often not designed for the turning forces that occur with offset impacts. Studies have shown that the brain reacts more sensitively to turning movements (offset impacts) than to linear movements (straight-on impacts). Unfortunately, there are currently no rotation tests within the EN 397 industrial helmet standard. Wearers should therefore be aware that the standard only represents the minimum requirements. Protective helmets are relatively good in absorbing linear impacts, as the EN 397 standard shows. The problem occurs when there is an impact and a rotational acceleration.

The helmet holds the head or skull when it turns, and turns it with the directional force of the impact. This happens not only when slipping, tripping, or falling over on the same or a higher level, but also through falling objects. This can include side impacts from machines too. The EN 12492 standard for climbing helmets and the EN 14052 standard for high-performance industrial protection helmets provide additional protection because these are tested for side, frontal or rear impacts. However, these impacts are always linear through the middle of the head. Also, the head form is fixed during the test so that no rotation of the head is possible, which is why the rotational protection is not measured using this test method.

The Mips safety system is able to provide significantly better protection. How does that work?

Max Strandwitz: The Mips safety system consists of a low-friction layer on the inside of the helmet that enables multidirectional movement of 10 – 15 mm during offset impacts. During an accident and a blow to the head, the Mips safety system will help to deflect the rotation of certain impacts that would otherwise be transmitted to the head. This minimizes the risk of brain injuries. Protective helmets that are fitted with the Mips safety system therefore provide additional protection beyond the standard.

Let us assume that I want to develop a safety helmet that incorporates the Mips safety system. How does the cooperation work and how does Mips confirm its effectiveness?

Max Strandwitz: As all Mips solutions are adapted to the respective helmet model and size, you have to contact Mips so that we can discuss together how the solution can best be integrated into the helmet.

Finally, it would be interesting to know in which areas of industrial protection you see the biggest potential for use...

Max Strandwitz: The building industry, oil and gas industry, mining, really all industries where there is the danger of an offset impact to the head. Everyone who has to, or should, wear a protective helmet as part of their PPE can potentially be hit at an offset angle, and the Mips system can therefore be their salvation.